The Mexican celebration of “Days of the Dead” in Oaxaca is a marvelous cultural experience. It dramatically highlights ancient beliefs about life and death and the interplay between pagan customs and Catholic rituals. For these several days in the fall of each year normal activities are suspended and the living and their departed ancestors are united once again. Cemeteries are transformed from places of the dead to rather magical realms of the living — be those living souls on this side of the Great Divide or on the other. Different villages have unique customs and celebrate the co-mingling of the living and the deceased on slightly different days, and in subtly different ways. But the over-arching theme is the same: a grand celebration of family tradition and the triumph of life.

From earliest times humankind has grappled with metaphysical questions. Where did mankind come from? What is the meaning of life? What sense can be made of the interplay between good and evil, life and death? Those who grew up in a Western culture have the philosophical insights of the Greeks and the religious principles of Jewish/Christian tradition to guide them. The ancient peoples of the Americas developed their own world view to explain the mysteries of life. The Aztecs, rulers of Mexico when the Spanish landed here in 1519, had a highly developed civilization that was, in turn, based on the 3,000 years of experience accumulated by the Olmecs, Maya and Toltecs who preceded them.

These pre-Hispanic peoples were comfortable with the dualities that characterize life. They saw life as being fluid and cyclical. The Aztecs believed the universe itself had gone through a series of births and deaths, and that they lived in the fifth incarnation of the world, which would come to an end when the god Quetzelcoatl returned. From their perspective, life and death were but two sides of the same coin. The realm of the living and the sphere of the dead were equally real, equally powerful and of equal value. Native peoples did not fear death, but saw it as a continuation of life on another plane. Instead of fearing death, they embraced it. To them, life was a dream, and only in death did they become truly awake.

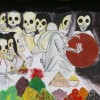

When people died, they were buried close to the living – often beneath the floor of the house – and there was great emphasis on maintaining ties with deceased ancestors, who lived on in a different place. The practices associated with the Mexican “Days of the Dead” grew out of the belief that spirits can return to earth to be with their families. For the Aztecs, the ninth month of the solar calendar (roughly corresponding to our August), was the time to celebrate this event. Month-long festivities were presided over by the goddess Mictecacihuatl, known as “Lady of the Dead.” Families would prepare offerings of food and things that the deceased enjoyed in life. These were laid out in the home. Candles would be lit to guide the spirits, and flowers (especially marigolds) and incense would be placed with the offerings, so the fragrance would welcome them. It was thought the spirits would consume the essence of the food and drink, and so be refreshed after their journey. Then the living family would enjoy the food and libations, often sharing them with friends and neighbors.

After the Spanish conquest, attempts were made to Christianize the indigenous people. Since the Catholic church had the practice of remembering the dead on “All Saints” and “All Souls” days, on November 1 & 2, the customs of the “Days of the Dead” were moved to those dates.

When the dictates of civilization caused people to be buried in cemeteries rather than beneath the home or in the yard, the tradition continued of the family building an “altar” in the home, decorated with food, flowers, candles, pictures and mementos of the dead. To it was added a procession to the cemetery, where the individual graves would be similarly adorned. The entire town would gather at the cemetery, where family members kept vigil through the night, often packing a hearty meal to be shared with the deceased.

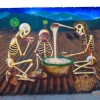

There are other popular customs associated with the Days of the Dead, too. In centuries past, people kept the skulls of the dead as mementos, the bones being a comforting, continuing presence of ancestors long gone. Nowadays, skulls made of sugar are placed on altars and graves, then eaten afterward. Plastic or papier-mâché skulls are extremely popular decorations. Living descendants frequently dress up in skeleton costumes, thus giving corporeal life to the spirits. Life-size “Catrinas” (skeletal figures dressed in fine clothing) pop up everywhere — in shop windows, on street corners, seated at restaurants, etc. Bakeries prepare special large, decorative loaves of “pan de muerto,” made with extra eggs and sugar, to be eaten at this special time. Some people with an artistic flair produce sand paintings, many with exquisite details, that may honor the dead, have a religious theme or show the interplay between the forces of life and death.

The American tradition of “Halloween” is also making inroads in Mexico, adding another layer to the celebration of “Dias de Los Muertos.” Children and adults alike delight in dressing in costume, then going trick-or-treating, parading through the streets (with brass bands and fireworks, naturally!) and dancing through the night. Since all of this is way too much for a single evening, the Days of the Dead go on for nearly a week.